I Stared Into the TV and It Stared Back At Me

The rise in consumer popularity of the television in the United States was a technological advancement with significant influence on public self-perception, the spread of information, the shaping of norms and standards, and the framing of social dialogue. This paper will examine how the role of television influenced and, was influenced by, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

The television and the Civil Rights Movement had comparable origins; both started to gain traction in the 1950s then erupted to an unprecedented level in the 1960s. This paper will demonstrate a key relationship between the rise of television and the content of its programming, with the progress of the Civil Rights Movement. In the first section the significance of the television will be highlighted. We will discuss its cultural importance and its evolution into the dominant form of media which became the “principal socializing institution in the United States.”1 With an appreciation towards the significance and societal implications of the television, this paper will expand on its relationship with the Civil Rights Movement. Broken into three key sections, this paper will detail how African Americans were represented on television in the 1960s. The second key area of focus will be on how African Americans fought for representation, who some of the key figures in the movement were for changing African American representation on television, and how they tried to achieve their goals. Finally this paper will highlight how the introduction of the TV, and its role in capturing images of the protests, violent repressions, and tragic moments of the civil rights demonstrations directly affected and propelled the entire Civil Rights Movement forward. The subtitle of this paper is “I stared in the TV and it stared back at me,” a play on the idea from the work of Friedrich Nietzsche.2 Nietzsche’s idea focused on being cautious of having yourself become that in which you focus your attention into; for this paper the idea is that your relationship with TV is a key factor for defining who you are in reality. Without representation, or with continued distorted representation, the Civil Rights Movement could not have progressed as quickly as it did. Without capturing and broadcasting the true nature of conflict the national consciousness would not have been made as aware of the Movement, and therefore it would not have succeeded in the measures that it had. The television played an integral role in this time period for the Civil Rights Movement.

Once the television began to gain traction in 1950s a broad audience was being displayed images never before seen, of which two areas will be focused on: the entertainment industry and the news industry. In the 1960s, African American watched 68% more TV than non-blacks.3 More African Americans watched TV than others, and in this noticed a lack of representation, biased reporting, and rampant racism. The TV had two ways of alienating and misrepresenting blacks, the first of which was by not accurately portraying their culture, or by distorting, insulting, demeaning or outright omitting them from narratives, the second way was by not allowing the grievances of African Americans to be heard or seen on TV. TV has the ability to validate and verify reality, “it may never occur to viewers to question whether a depiction is real; and if they do, they may conclude that the show is essentially true, it is ‘telling it like it is.’”4

The television acts as an intrusive and validating structure which upholds the public perception of what is true in society. The TV in many cases does all the thinking for you, “most people do not have the time, intelligence, or even interest to think through political issues after a careful reading of news reports and analyses.”5 Televised programming digested by an audience adds to the viewer’s perception and understanding on given topics. This is especially true for reinforcing norms.

One problem with TV is that it uncritically reflects “the social structure of society in its selection and presentation of characters associated with class divisions.”6 This reflection of society was viewed by African Americans to be very distorted and painted a misrepresented picture – one entrenched in racism.

Blacks in 1950s television were excluded unless they were “entertainers, bumbling idiots such as Stephen Fletcher, or devoted servants such as Rochester in the “Jack Benny Show” or Willie Best in “Life of Riley.””7 When given more dominant roles in the 1960s, a few trends became apparent. One example is the “black hero”. The “black hero” was a trend in mainstream television of giving blacks acting roles which ultimately upheld the white establishment. Two examples of this trend are violent superheroes and Bill Cosby.

“Since the introduction of the ‘I Spy’ series in 1965, blacks have been portrayed as violent superheroes who defended the white establishment in over 95% of the dramatic series in which they have been regularly featured.”8 This cannot be understated, a massive majority of TV programs that had featured blacks were crime related and structured in ways to make “black heroes” appear as good actors, this gave legitimacy to the status quo and upheld the white establishment along with the societal norms.9 Black were consistently given roles slanted to support the white establishment.

The “Bill Cosby Show” further misrepresented blacks. The show was welcome on the air because the Cosbys took on the roles and norms of white society; they were based on an upper middle class standard white American family and household. The show had, what Kiuchi argues, “accidental blackness” they were a family “who by accident happen to be black” but they “spoke white, acted white and made a replica white family.” In his book the Struggles for Equal Voice: The history of African American media democracy, he makes the argument that the “Bill Cosby Show” while starring an African American actually contributed to the problem of misrepresentation which made the “public feel colourblind”. Since there were blacks on TV it made whites audiences believe, “race was no longer a problem.”11

Further examples of racist or misrepresented shows in the 1960s were the Jackson based “Forum” which stressed pro-segregationist views coupled with pro-racism and anti-communism, calling the Civil Rights Movement a “paper curtain” damaging the Freedom of America.12 The evening news in Jackson on WJTV often used degrading language, use of the word “nigger”, unprofessional and severely biased reporting, as well as intentionally distorting the image of the Civil Rights Movement.13 This racism and misrepresentation, while often stronger, was not limited to the Southern States. In Chicago, John Sengstacke, editor and publisher of the Chicago Daily Defender, stated “The negro as a normal human being doesn’t exist in the programming eye of the local Chicago television stations.”14 Bill Monroe, former news director in New Orleans during the 1960s, stated that the bias against African American was “frequent and pronounced.”15 One memory he recalled was that Southern broadcast stations would often “not use film showing police brutality even though their own cameraman had shot it”, the reasoning was a concern that allowing viewers to see the footage may lead to “demonstrations and disorders”, he stresses, “two words often used interchangeably in the South.”16

One of the key proponents for proper representation of African Americans on TV was Medgar Evers from Mississippi.17 Evers, starting in the 1950s, held campaigns and filed petitions which were “challenges to segregationist broadcast practices.”18 Evers argued that the local media created a “distorted and slanted view of conditions faced by black Mississippians,” he continued, the African American point of view “was not being seen or heard in local or network presentations.”19 Medgar Evers and many other activists sought to gain larger representation, reduce the amount of racism, open up an avenue for discussion, and create a platform to raise grievances. The main way that activists sought change was with petitions, formal protests, lawsuits, and using federal institutions such as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).19 These early petitions against stations such as the WJTV and WLBT in Jackson were instrumental in shaping the future discussion of TV rights and proper representation. Through the use of the FCC, broadcast law, and activist resources of northern reform organizations, local activists submitted a five-page “petition to deny licensing” with the goal of ending the licenses of WJTV and WLBT.20 The full ramifications and following events are too detailed for this paper to explore, however a few key points are worth noting. One point being the inherent success of these petition movements, local stations now had a watchful eye on them, broadcasting became more of a consumer concern, and a precedent was set for legal and social action for groups like the FCC to use upon other racist or segregationist TV stations.21 The ramifications of this, the increase of blacks on TV following these petitions, and the continual progress of the Civil Rights Movement leads into our final section.

When white people first began to see black people on TV there was an inherent shock. Viewers were surprised by seeing black people on the air, especially when they saw someone like the head of the NAACP speak articulately and pushing for civil rights live on TV in Mississippi in 1963.21 Activists like Evers were aware of the power of TV. They saw that TV was “vital to the struggle not only over the representation of race, but over a different way of life.”22 What propelled the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s forward was the introduction of civil rights campaigns, protests, attacks, and general awareness onto the local and national TV stations. When Northern States saw Southern protests and violence they were shocked, when other blacks saw it they were angered, and when enough attention and awareness was brought to key civil rights moments the information carried all the way to the White House. “Images of struggle distributed by television helped them gather a sympathetic audience for their cause.”23

The first key event which caught national broadcast attention involved 15 year old Elizabeth Eckford in 1957 at Little Rock.24 When black students were finally given permission to go to the local school a crowd of white racists came to protest; Elizabeth arriving late was confronted by the mob. News crews filmed the older white men surround the small black girl screaming appalling slurs like “lynch the nigger.”25 The incident prior to the introduction of TV, may have had a local headline like “black girl harassed by white men”, or even more likely had no story at all, but with the introduction of television, this tragic and horrific harassment and verbal abuse of the girl was shot into the national mainstream TV stations. This event reached a large level of audience with raw footage that connected to people more deeply than before. The filming of the event and the uproar that followed went so far as to catch the attention of President Eisenhower who ordered national troops to protect students from any other threats.26 The early 1960s “Freedom Rides” also received much national attention. While the direct attacks and mobs were not filmed and shown to viewers, the consequences and injuries were. Following the brutal assault in Alabama national stations showed images of battered men and women which captivated people’s anger.27

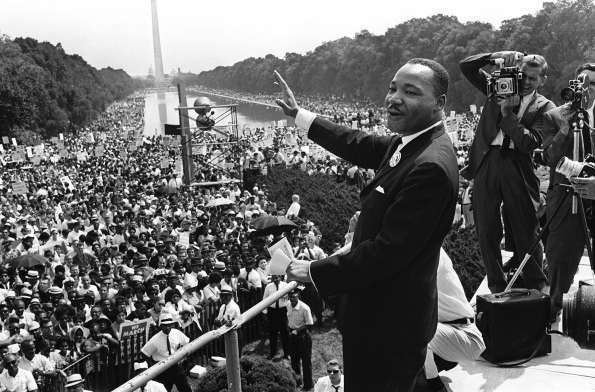

Television had the power to define reality, to create understandings for societal norms, and to shape opinions. The African American activists knew this and “sought greater access to, and participation in, the mass medium.”28 The activists knew the importance of proper representation, and knew the affect that showing the protests and violent oppressions would have on the national audience, so much so that it was reported that Martin Luther King would sometimes cancel marches and protests when he found out that a news reporting team would not be present.29 Another massive televised uproar occurred during the 1960s Birmingham protests.

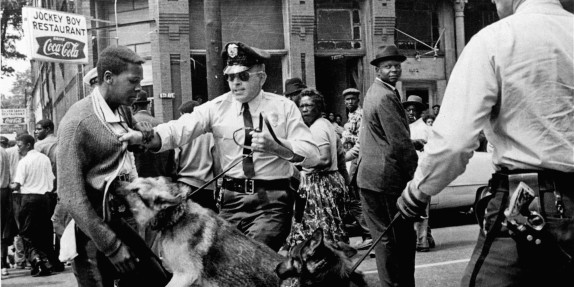

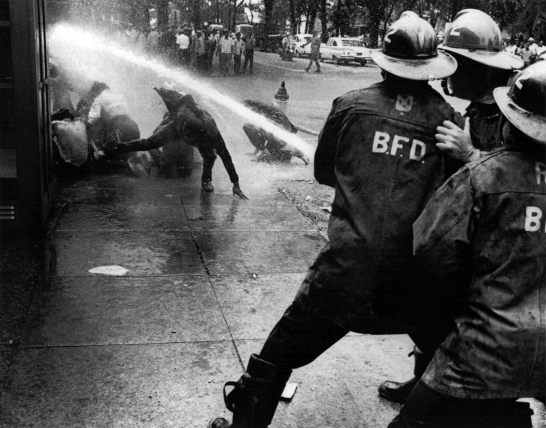

African Americans were shown to be participating in non-violent peaceful demonstrations and sit ins, shortly after whites began harassing and attacking the protesters. Mayor Connor of the city, having enough of the protests, ordered physical assaults and the use of fire hoses on the protesters including the women and children.30 When that didn’t work, he ordered police dogs to attack the protesters. The American people witnessed a “new level of police brutality.”31 The camera rolling captured one of the most powerful videos of the Civil Rights Movement. A young black boy was held down to the ground with multiple police officers beating him and holding him in a position allowing the dog to maul the defenceless boy. As a result of the “filmed protests and brutality, President Kennedy began more federal actions and pressure.”32 Kennedy in a speech soon after said, “We preach freedom around the world, but are we to say to the world, and much more importantly to each other, that this is the land of the free, except for the Negroes?” he continued, “The time has come for this nation to fulfill its promise.”33

Historian Doug Owram writes, “Every new civil rights effort brought pictures of police dogs attacking protesters, of fire hoses trained on demonstrators, and of the courage of peaceful protest in the face of thuggery.” Furthermore he wrote, “Television was bringing something new into the homes of North Americans.”34 Other programming such as the massive coverage of the March on Washington, many speeches by MLK, as well as the iconic 1963 film “American Revolution”, also helped raise public awareness. “American Revolution” was a film that showed scenes from both the Little Rock and Birmingham conflicts and which caused the New York Times to state “never before has so much valuable prime time been accorded to a single domestic issue in one uninterrupted stretch.”35

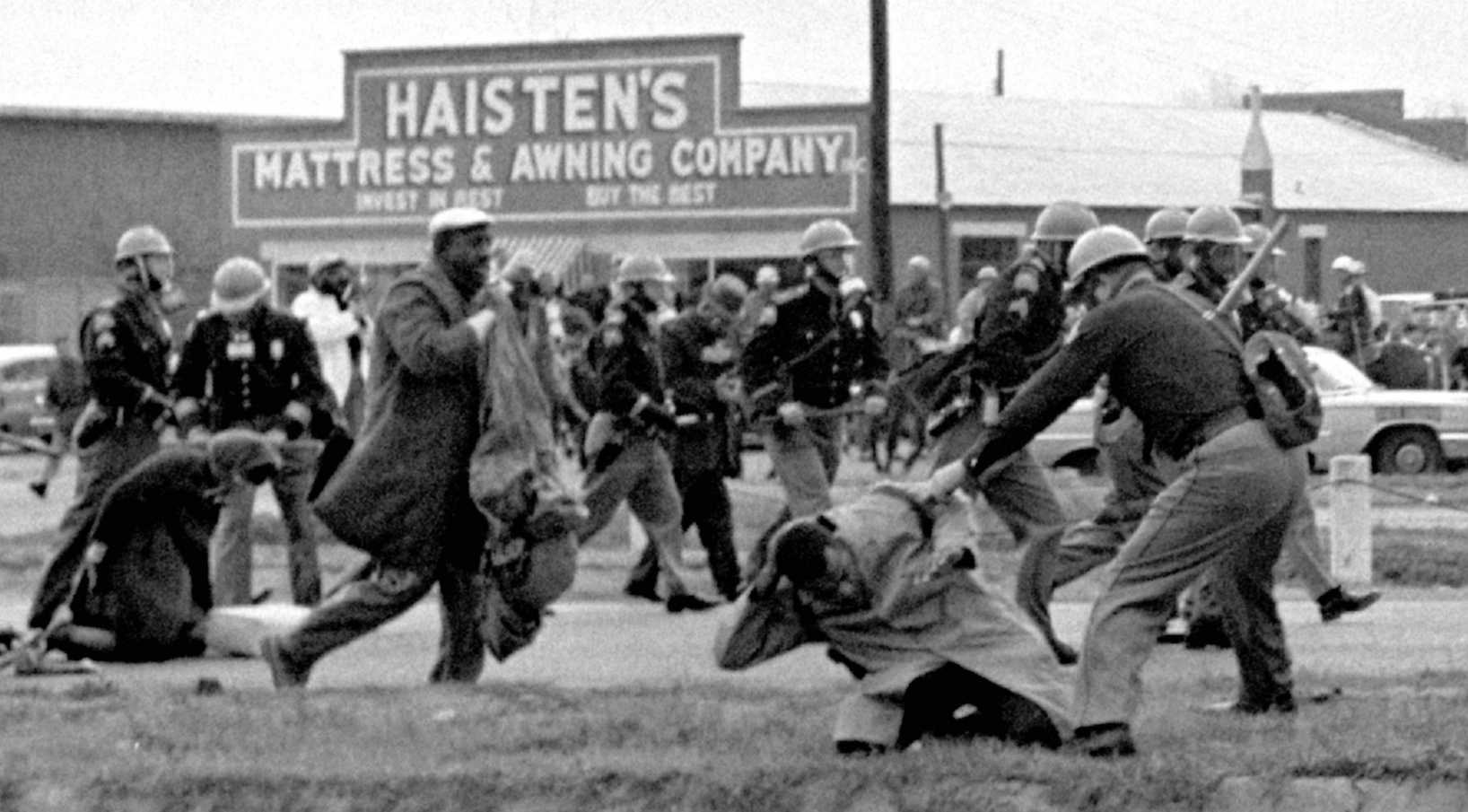

The final moment this paper will examine, which arguably was the most significant for its broader implications, was the civil rights march in Selma on March 7 1965, later dubbed “Bloody Sunday”. Protesters were beaten, tear gas was used, middle age women were held down and kicked, men on horses clubbed peaceful protesters, and bullwhips were used on blacks who were nowhere near the demonstration.36 The televised event ignited a powdered keg, huge political movements followed afterwards, and specifically due to the television broadcasts, the event was thrown into the national consciousness. President Johnson told Governor Wallace “the brutality in Selma last Sunday must not be repeated.”37 The next protest in Selma two weeks later occurred with national attention and without violence.

Due to the television, what before was contained in small localized protests, now was projected onto the national platform and gained federal attention. People were now able to intimately in their homes view and understand the conflict. The nation did not support what it saw occurring in Little Rock, in Birmingham, in Selma and in repeated conflicts. Shortly after the tragedies in Selma and President Johnson’s political outrage, congress passed the two defining Acts of the Civil Rights Movement, the “Civil Rights Act of 1964” and the “Voting Rights Act of 1965.”37 This paper has demonstrated a direct link between the Civil Rights Movement, its representation on TV, and the national attention that followed. In this period during the Cold War, the American audience viewed a “western democracy using the forces of the state to deny rights to its own people.”39 The visual portrayal and national broadcast of oppression on African Americans struck a nerve in society, that went all the way to the White House generating action from Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson. The success and power of the television broadcasts ushered in a new era of protest, resistance, and cultural awakening.

In conclusion this paper has demonstrated multiple points. First that African American’s felt misrepresented in local TV broadcast stations especially in the South. African Americans sought two different forms of TV representation. First as characters on shows with an accurate portrayal of their culture, and secondly as activists with a legitimate platform to express the goals and grievances of the Civil Rights Movement. To achieve this, activists such as Medgar Evars launched aggressive campaigns and petitions with federal groups such as the FCC. This ultimately resulted in fairer representation on local stations and a new standard for consumer concern on TV programs. These facts are coupled with an appreciation for the significance of TV in the American society and the powerful new role it played. By the end of the 1960s, over 78 million of America’s 202 million people owned a TV set.40 The TV was significant in two ways, first as a medium to create legitimacy and validity. African Americans needed to gain fair representation on TV in order to reach that same level of equality and legitimacy in reality. The TV acts as a reflection for the norms, values, and standards of a society. The second reason that the TV was significant was because it directly affected and propelled the Civil Rights Movement onto the national platform, which in turn brought heavy federal and public attention, sympathy, and support. The TV “brought into living rooms for the first time powerful images of demonstrations and racial violence.”41 Following Selma an NBC commentator said “The Civil Rights Act suddenly has the support it needed, those images changed history.”42 The television enhanced the “black community’s own political, psychological, and cultural consciousness, unity and power.”43 The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s holds a powerful and integral relationship with television. The television and program content not only changed with the Civil Rights Movement, but more powerfully, the Civil Rights Movement would not have been as quick or even as successful without the use of the television to raise the national consciousness, spread societal awareness, and ultimately lead to a stronger and more equal society in America.

By Daniel Govedar (Written Nov 2014, Edited February 2017)

End Notes

- Taylor, H., & Dozier, C. (1983) Television Violence, African Americans and Social Control 1950-1976. 107

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. (1997) Beyond Good and Evil. 52

- Kiuchi, Y. (2012).Struggles for Equal Voice: The history of African American media democracy. pp. 25

- Taylor, H., & Dozier, C. pp. 109

- Chakravorti, Robi. (2005). Politics as Show Business. 279

- Taylor, H., & Dozier, C. pp. 109

- Taylor, H., & Dozier, C. pp. 125

- Taylor, H., & Dozier, C. pp. 126

- Taylor, H., & Dozier, C. pp. 131

- Kiuchi, Y. pp. 27

- Kiuchi, Y. pp. 28

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. (2004).Watching Jim Crow: The struggles over Mississippi TV, 1955-1969. 38

- Williams, Jullian. (2002). Broadcast Segregation: WJTV’s Early Years. 91

- Benson, Devyn Spence. (2012). Owning the Revolution: Race, Revolution, and Politics from Havana to Miami, 1959-1963. 117

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 48

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 44

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 43

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 44

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 3

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 62

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 47

- Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 48

- Kiuchi, Y. pp. 25

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. (2012).Mightier than the sword: How the news media have shaped American history. 158

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 158

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 158

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 160

- Benson, Devyn Spence. pp. 117

- Kiuchi, Y. pp. 29

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 161

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 161

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 163

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 163

- Schwartz, Mallory. (2010). Like “Us” or “Them”? Perceptions of the US on the CBC-TV National News Service in the 1960s. 121

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 166

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 168

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 169

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 169

- Schwartz, Mallory. pp. 121

- Culbert, David. (1998). Television’s Visual Impact on Decision Making in the USA, 1968: The Tet Offensive and Chicago’s Democratic National Convention. 420

- Williams, Jullian. pp. 87

- Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. pp. 169

- Benson, Devyn Spence. pp. 119

Work Cited

Benson, Devyn Spence. (2012). Owning the Revolution: Race, Revolution, and Politics from Havana to Miami, 1959-1963. Journal of Transnational American Studies. Vol,. 4. No.2 (2012) pp. 1-30.

Chakravorti, Robi. (2005). Politics as Show Business. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Jan. 22-28, 2005), pp. 278-279. Economic and Political Weekly. DOI: 10.2307/4416099

Classen, S. D., & American Council of Learned Societies. (2004). Watching Jim Crow: The struggles over Mississippi TV, 1955-1969. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Culbert, David. (1998). Television’s Visual Impact on Decision Making in the USA, 1968: The Tet Offensive and Chicago’s Democratic National Convention. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 33, No.3 (Jul., 1998), pp. 419-449. Sage Publications. Ltd.

Kiuchi, Y. (2012). Struggles for Equal Voice: The history of African American media democracy. Albany: SUNY Press.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. (1997) Beyond Good and Evil. Dover Publications. (Trans.) Zimmerman, Helen. (Original Work Published 1909)

Schwartz, Mallory. (2010). Like “Us” or “Them”? Perceptions of the US on the CBC-TV National News Service in the 1960s. Journal of Canadian Studies. Vol,. 44. No.3 (Fall 2010) pp. 118-153

Streitmatter, R., & Ebooks Corporation. (2012). Mightier than the sword: How the news media have shaped American history (3rd ed.). Boulder: Westview Press.

Taylor, H., & Dozier, C. (1983) Television Violence, African Americans and Social Control 1950-1976. Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Dec. 1983), pp. 107-136. Sage Publications, Inc.

Williams, Jullian. (2002). Broadcast Segregation: WJTV’s Early Years. American Journalism. Vol., 19. No. 3 (2002). pp. 87-103. doi: 10.1080/08821127.2002.10677890

very helpful information

LikeLike